Ar. Rahul Kadri, IMK Architects

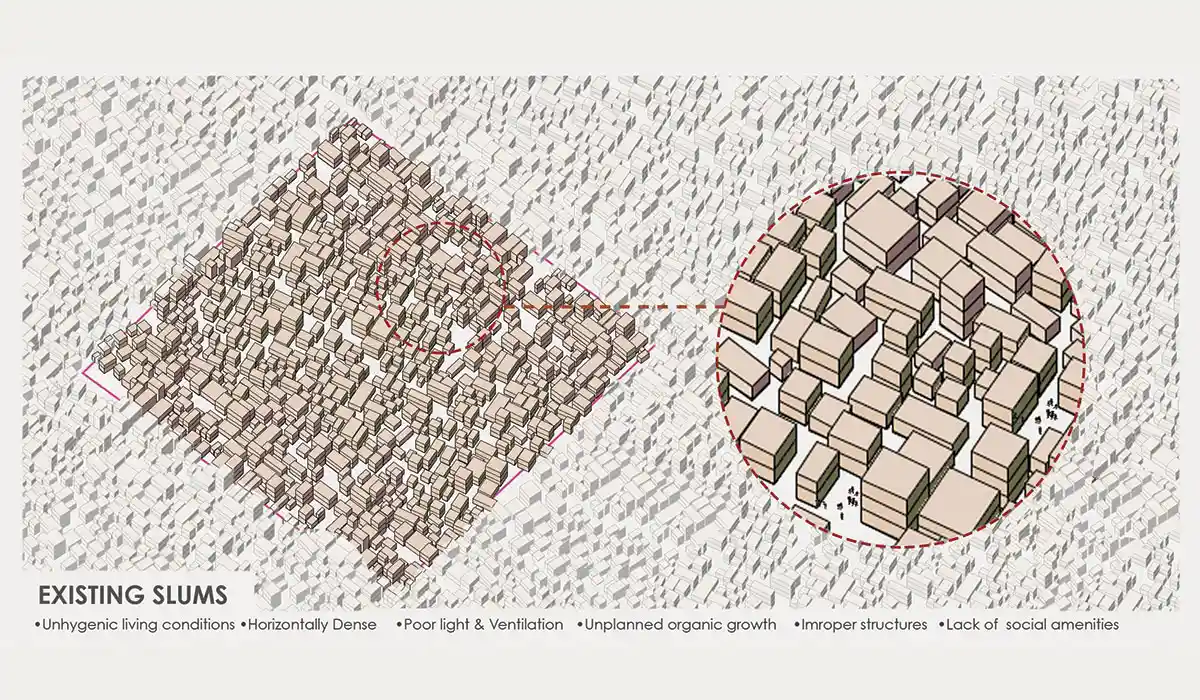

The coronavirus outbreak has put a spotlight on the often-overlooked underbelly of India’s ‘City of Dreams’ –– the slums and other informal settlements where about 49 percent of its population resides. These neighbourhoods are characterised by unusually high population densities of up to 350 families per hectare against Mumbai’s average of 38 (as per data from the 2011 Census) and poor drinking water and sanitation facilities, giving rise to unhealthy living conditions. So, what is the future of slums in a post-Covid world? Can we formalise the informal?

Lopsided Developments

Cities are envisaged as the hub of economic, social, and technological advancements and opportunities, which brings in an incessant flow of migrants to them. However, widening gaps between growing city populations and the physical and social infrastructure required to accommodate them is leading to a lopsided pattern of urban development and increasing urban poverty.

With a premium attached to limited land and space, land and building stock prices have skyrocketed. This pushes incoming migrants, who make up the majority of the city’s population, to seek housing within low-cost, poorly designed shanties and tenements in informal settlements with extremely poor living conditions. As per the Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SRA) city survey data, 49.38 percent of Mumbai’s population, accounting for around 4.6 million people, lives in slums that occupy barely 7.5 percent of the city’s area.

The Birth of Vertical Slums

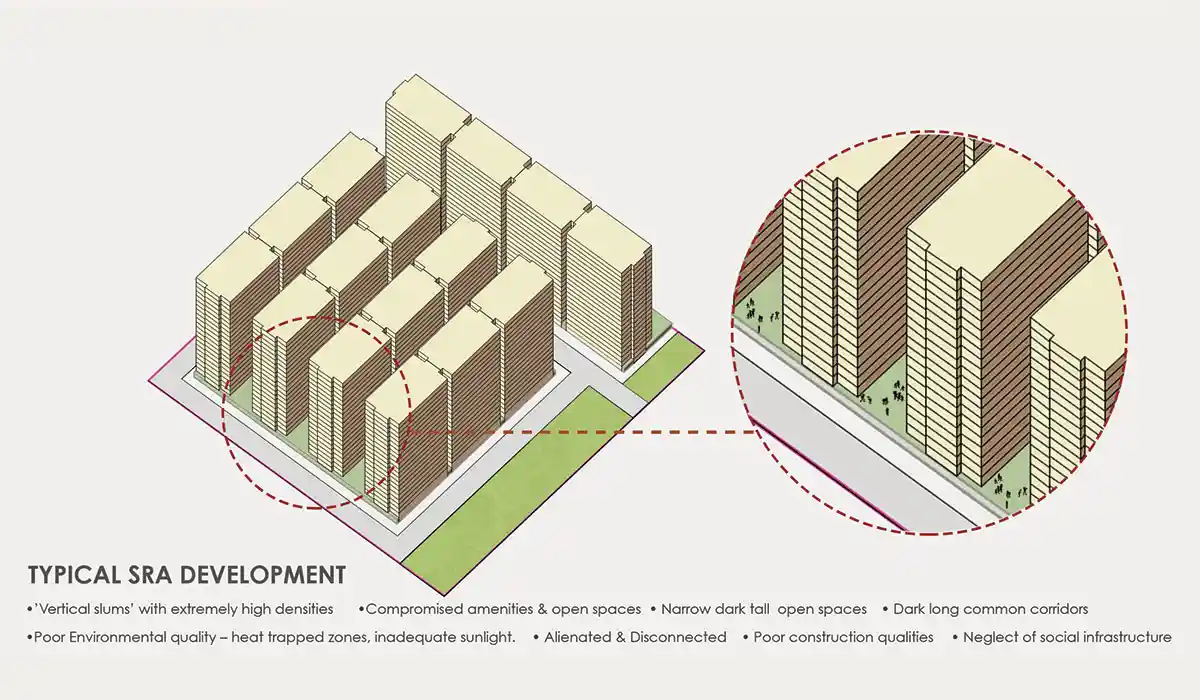

To alleviate the plight of people living in slums, private sector players introduced models of subsidized rental housing. However, lured by the assurance of FSI (Floor Space Index) and TDR (Transferable Development Rights) incentives in 1995’s ‘Slum Rehabilitation Scheme’ (SRS), the needs of slum dwellers were shelved to prioritise profits to builders and developers.

SRS facilitates the redevelopment of slums through the concept of land-sharing where open sale of housing units in the market allows the cross-subsidising of free units for the slum dwellers. However, the full authority and discretion on decisions concerning the quality of construction lies in the hands of private developers, which has turned this scheme into a crooked and ineffective mission.

Drawbacks of Builder-Led Redevelopment Schemes

Driven by profit margins, developers use up to 75 percent of the available land to build units that they can sell, while forcing the existing slum dwellers into the remaining 25 percent, transforming horizontal slums to vertical ones in the name of high-rise development.

Within these matchboxes in the sky, occupant discomfort and health issues are rife. Living spaces are cramped and dark; they feel too hot or too cold and are inadequately ventilated leading to poor indoor air quality. These buildings also neglect how ‘life on the street’ is inherently tied to the socio-economic fabric of informal settlements; the lack of recreational and community spaces restricts occupants from engaging in community or livelihood activities that were an integral part of their life in the slums.

This incompatibility between low income and the high cost of living in the city, as well as the dissatisfaction with the new rehabilitation buildings, forces distressed residents to move back to slums or to look for new squatter settlements.

The Case for Self-Redevelopment

So, are there better alternatives? How can slums be redeveloped in a manner that ensures affordability, inclusivity in decision making, improved quality of life and socio-economic wellbeing of the community?

Self-Development of Slum Communities (SDSC), a process where slum occupants take on the mantle of redevelopment themselves supported by the expertise of appropriate professionals, might provide the solution.

SDSC is aimed at accelerating the entire process of redevelopment with the self-intent of the community. It makes the association of residents the primary stakeholders in the process, leading to a transparent and inclusive design process that directly and efficiently addresses their needs and concerns and fulfils their expectations of better living conditions. SDSC can be easily incorporated within city development plans by transferring the development rights of land parcels marked as slums to the association of the current inhabitants of that neighbourhood.

The government needs to reduce permissible FSI to ensure that ‘vertical slums’ do not take form again. Instead, it should discontinue levying the charges that it does to reduce project costs significantly. This would allow residents to fund the construction through personal loans along with liquid capital raised by the sale of new units from the development. The loans could be repaid with monthly EMI instalments with appropriate subsidies, which would be far lower than the unusually high rents that occupants pay for remarkably low square footage.

Envisioning a Slum-Free City

It is important to understand that the vision of a slum-free city needs to be viewed through the lens of inclusive development. Elimination and clearance of slums has to be substituted for up-gradation of living conditions, provision of access to basic services, and participation of the current slum dwellers in policy conception. Only with a multi-faceted approach to redevelopment that incorporates economic, environmental and cultural sustainability,

Rahul Kadri is a Partner & Principal Architect at IMK Architects, an architecture and urban design practice founded in 1957 with offices in Mumbai and Bengaluru. He holds a graduate diploma in architecture from the Academy of Architecture, Mumbai, and a Masters in Urban and Regional Planning from the University of Michigan, USA.